Share

By Zoya Mateen

BBC News, Delhi

Who invented butter chicken?

The velvety dish, made in a thick tomato-yoghurt gravy with rich notes of butter and mild spices, has inspired mystery novels, travelogues, and countless restaurant orders.

But the comforting curry that people from around the world turn to as a familiar favourite has now become the subject of a messy court battle.

A lawsuit over the dish’s origins was filed in the Delhi High Court last week. The case involves two competing restaurants and families, each claiming a lineage with the city’s renowned Moti Mahal restaurant founded in 1947, and each calling themselves the inventors of the popular dish.

The lawsuit – brought by the family of Kundan Lal Gujral, one the original restaurant’s founders – claims that Gujral created the curry and has sued rival chain Daryaganj of falsely taking credit for it.

The Gujral family, which is seeking $240,000 (£188,968) in damages, has also alleged that Daryaganj has wrongly claimed it invented dal makhani, a lentil dish made with butter and cream.

But it’s butter chicken that has dominated headlines.

There are countless versions of how butter chicken was invented, but all of them start with a man called Mokha Singh, feature three of his employees and involve at least three different restaurants located across the subcontinent.

The lore goes back to pre-Independent India and inside the dusty lanes of Peshawar (now in Pakistan), where a young Singh ran a popular restaurant called Moti Mahal, says chef and food writer Sadaf Hussain.

In 1947, when India was partitioned, Singh and several of his Hindu employees fled Peshawar and moved to the Indian capital. Soon they lost touch with each other.

Until one day, when three of them – Kundan Lal Gujral, his cousin Kundan Lal Jaggi, and Thakur Das Mago – ran into Singh at a makeshift liquor joint, and convinced him to let them open a new Moti Mahal in Delhi.

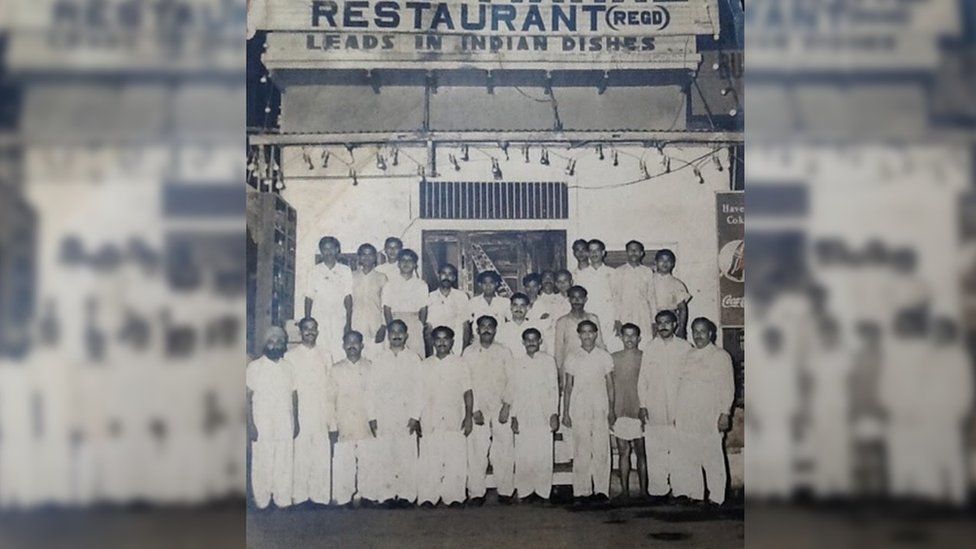

It was at this small open-air diner, located on the crowded Daryaganj street in the old quarters of Delhi, that butter chicken was born, Mr Hussain says.

The idea was born out of frugality, using leftover tikkas and mixing it in a thick tomato gravy and dollops of butter. But it did wonders.

Within a year, ministers and heads of state, including India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, had become regular customers at Moti Mahal. “Peace treaties were hammered out in the balcony. And M Maulana Azad… reportedly told the Shah of Iran that while in India he must make two visits – to the Taj Mahal and Moti Mahal,” The New York Times wrote of Moti Mahal in 1984.

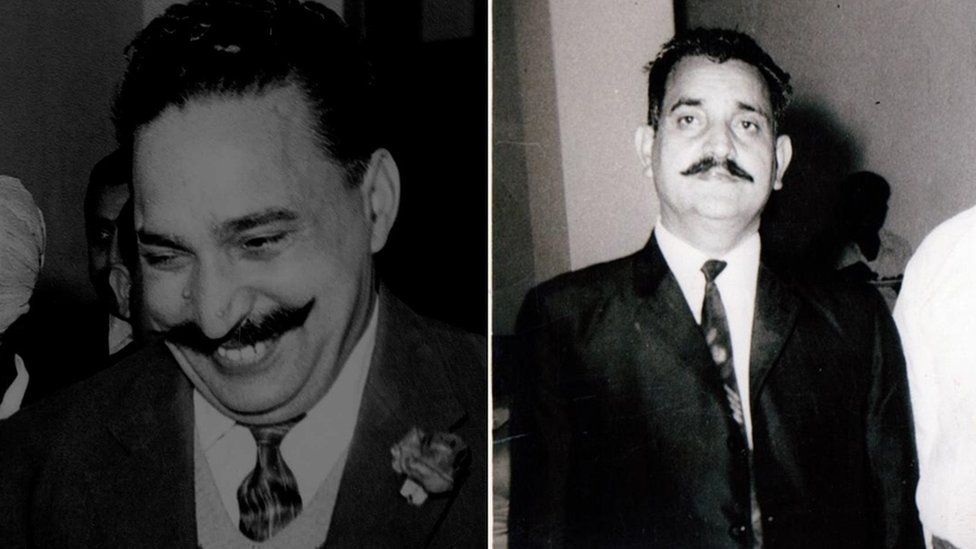

For a long time, Kundan Lal Gujral – whom the newspaper described as “a portly, florid” man with a “splendid moustache” – was credited for the booming success.

But things changed after his death, Mr Hussain says. In 1997, the Gujral family had to lease out Moti Mahal after facing financial difficulties. (The restaurant is now run by a different family)

A few years later, the Gujrals launched a separate chain – this time calling it Moti Mahal Delux – and returned to business, opening franchises across the city.

But another setback awaited them in 2019, when the grandson of the second partner, Kundan Lal Jaggi, opened a rival chain of restaurants called Daryaganj, added the description “By the inventors of Butter Chicken and Dal Makhani”, and trademarked it.

The owners of Daryaganj argued that while Mr Gujral was the face of the restaurant, Mr Jaggi handled the kitchen and so the dishes, including butter chicken, were all his ideas.

The Gujrals, however, rejected this and claimed that Mr Jaggi was a junior partner who did not play a major role in the making of the menu, and that butter chicken, in fact, was created by Mr Gujral while he was still in Peshawar.

That’s the battle currently playing out in court: the family is demanding that owners of Daryaganj be restrained from calling themselves the inventors of butter chicken. “You cannot take away somebody’s legacy,” Kundan Lal Gujral’s grandson, who has filed the lawsuit, recently told Reuters news agency.

This is not the first time that someone has gone to such lengths to claim ownership of a dish.

A bitter tussle broke out between the eastern states of Odisha (formerly Orissa) and West Bengal over which of them invented the rasgulla, a plump sweet milk and cheese dumpling lathered in a sugary syrup. The question was finally put to rest in 2018, after Geographical Indication (GI) authorities ruled in favour of Bengal.

In recent years, chefs too have invoked intellectual property rights to defend their restaurants, their signature style and dishes, although it’s still rare for a case to reach the courts.

But such disputes are usually commercial in nature and have little to do with customers, says food writer Vir Sanghvi. “People go to restaurants to eat dishes they like and don’t really care who invented them decades ago.”

He adds that sometimes, dishes become so popular that their inventors are forgotten. “Who created the first masala dosa? Some versions give the credit to the Woodlands restaurant chain. Others dispute this and nobody cares enough to dig deeper.”

Mr Hussain agrees. “How food travels is magical. It could be through parallel sources,” he says. “People move, they take their recipes with them, adjusting it to local palates along the way.”

He gives the example of the UK, where a Pakistan-born restaurateur from Glasgow is widely credited with the invention of chicken tikka masala. But many cooks, especially at Bangladeshi restaurants, claim that they came up with the recipe. Others say the masala wasn’t invented in Britain at all, but came from Punjab.

That’s why the fight for butter chicken is also inconsequential, he adds, because the dish goes beyond one restaurant and is found everywhere. “You might get credit for inventing it, but what truly matters is who serves better quality,” says Mr Hussain.

In Moti Mahal’s case, things are likely to be trickier because the dispute isn’t about whether the restaurant created butter chicken; it’s about which of its owners played a bigger role in its invention.

“It is the story of two men fighting for their grandfathers’ legacies. And those disputes are often the hardest to settle,” Mr Sanghvi says.

According to lawyers, the court would have to rely on “circumstantial evidence” and testimonies of people who had the dish decades ago. But even then, how would the judges determine who made the first pot?

It is possible that one of the partners had a handwritten recipe which could help settle the issue, Mr Sanghvi says. “So far this has not come to light.”

But the owners of Daryaganj know that even if they retract their claims about inventing the dish, it would make no difference to their business. And despite the success of Daryaganj, Moti Mahal would continue to flourish as well, Mr Sanghvi adds.

“Either way, it is going to be hard to tell, so https://perjuangangila.com/ many decades later, what really went on in the kitchen.”